Review of 'Blown By The Wind' (1971)

Our review of Blown By The Wind (1971) directed by Jacques Madvo, with a brief discussion of the Six-Day War of 1967, Palestinian agriculture, and Palestinian music.

Welcome to Narratives of Resistance: Festival Film Recap! This post is part of our series to review films that were screened during our last festival, while we prepare for our upcoming set of film festivals in November 2025. Blown by the Wind (1971) directed by Jacques Madvo was screened in the London, Hong Kong, Kuala Lumpur, and Rotterdam editions of our 2024 festival.

Curious about our film festivals? Check out our Substack post here or Instagram story highlights on @nor.films!

3 out 5 stars, experimental short film

Peace is his dream, and he’s eleven years old.

— Jacques Mavdo, Blown by the Wind (1971)

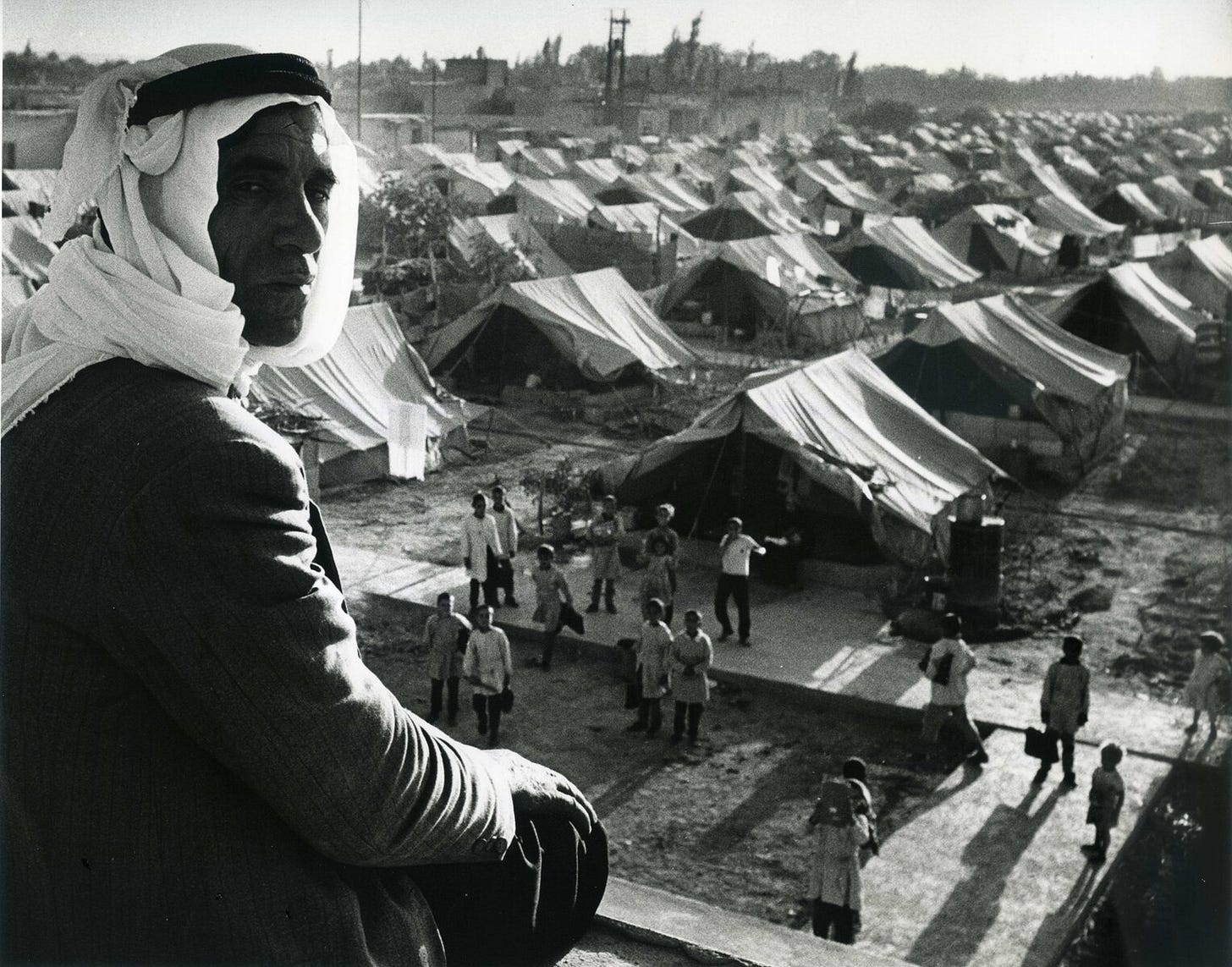

Jacques Mavdo’s ‘Blown by the Wind’ (1971) is a bleak yet hopeful portrait of the imaginations of displaced children following the brutality of the 1967 Six-Day War. In just under 18 minutes, it tells the story from the perspective of children without childhood of a people who had to flee their homes in Palestine as violence ensued between Israel and the coalition of Egypt, Syria, and Jordan. It is not so much as a film but a documentation and collage of the actual and represented experiences of Palestinians, especially children affected by violent conflict. Behind each admittedly messy painting is a child who hoped for their home to exist and their community unravaged by war. In another world, these children would have turned their passion for painting into masterpieces like the mural By War Child UK in Euston Square. Yet the harrowing reality is that they most likely never had the opportunity to develop their gifted hands.

Before a narrator prologues the film along with snapshots of desecrated farmlands, we hear the susurration of wind. It endures in the background even as the narrator tells us of the “bombs and gunfire [that] made a shambles of clay-built villages,” and how “in many of them, Palestine refugees have lived for 20 years.” We also see the faces of some men, women, and children, while others have distressingly covered theirs. Those whose faces we still see wear despondent gazes. They have just lost the physical connection to their land, livelihood and home—and yet the wind persists.

It isn’t until the paintings are shown that the wind dies down and traditional Palestinian music takes over. Accompanying the fast-paced jingles, a new landscape emerges: vibrant and full of life, in stark contrast to the black-and-white images of the prologue. We see people resting, working on farms, children playing, and women with baskets in their arms. This is what life could have been: harmonious—nature surrounding the people, and people living in their community, their community thriving because of nature. Trees, specifically orange trees bearing many fruits make a cameo among the paintings. We see farmers harvesting these oranges—most likely the internationally recognised Jaffa oranges or Shamouti, which remain a symbol of Palestinian pride and resistance to this day. Their long history as a Palestinian trademark can be traced back to mid-19th-century Jaffa, an ancient Levantine port city in Ottoman Palestine. The farmers there took a sport mutation and designed specific grafting techniques to “evolve a new variety of citrus”. Its small number of seeds, “sweetness and thick, easy-to-peel skin” makes it the ideal fruit for export and consumption. As a result, the farmers heavily relied on them.

However, when the Ottoman Empire began to fall, it began to sell the land under its control, despite the land not being officially state owned. According to Nahla Abdo, it became “the property of the state only when capitalist, colonial and imperial power is imposed on [the] colonised land.” And so Jaffa orange groves that were originally owned by the farmers and workers were targeted and the land was appropriated, most notably by Rothchild or his Palestine Jewish Colonization Association. By the late 1930s, Jewish settlers owned roughly half of the 60 thousand dunams (approx. 60 million m2) used for orange orchards in the country. Today, tree planting in expanded Israeli settlement areas is a growing method of resistance, serving as tangible reminders of connecting Palestinians to their roots and to their land.

As the music continues, a chorus of singers joins in, and the paintings become more vast, overseeing the entire village. Suddenly, it stops. The wind picks up again. It seems like the wind, but something’s off — it sounds like there’s much more force behind it. Like a rocket. No… missiles. Scenes of war erupt. Violence has caught up to this village. Red and black strokes fill the screen, accompanied by the sounds of guns and bombs. The camera shakes with quick zooms, capturing the despaired faces that hark back to the prologue. Over the gunfire, the voice of a child can be heard recounting the death of his mother. When the sounds of war stop, the wind picks back up again to fill the silence. The film ends with images of a warm sun and the narrator’s exposition:

“The dreams and hopes in these youngster’s paintings are our best hope for the future.”

Watching and then discussing the film in the London festival with Palestinians in the room was undoubtedly quite odd. At first, it was known that they have personal connections to the film and therefore they led the talks. And as the room listened to childhood stories, in particular one about a grandfather’s tree in the back garden and how they used to climb up and play there but now it’s no longer there anymore, the paintings in the film began to feel less abstract. Given the events in Gaza and the West Bank, Palestinians remain displaced, their homes destroyed, and many lives lost. At the time of writing this, over 62,000 Palestinian lives have been lost since the Israeli government started the genocide in October 2023. Almost a third of these lives belonged to children but both numbers may be higher with unrecorded deaths. Though it was produced over five decades ago, Mavdo managed to create a film with a message that remains relevant for as long as the genocide and occupation continues. It is through hope that the children today in Palestine resist the terrors of violent injustice.

Jacques Madvo

Jacques Madvo (also known as Jack Madvo) was born in 1924 in Armenia, in a geographical region that is now considered a part of Turkiyë, just a few years after the Armenian Genocide. His mother passed during childbirth and shortly after, his father was killed, which left Madvo orphaned at a very young age. He went to live with his aunt and her two daughters in Beirut, Lebanon. There, he grew up believing that his aunt was his mother, and that her two daughters were his sisters. Madvo’s aunt passed away when he was 12-years-old.

Madvo studied medicine at La Sorbonne Université in Paris, France, but fell gravely ill during his course. He took a leave of absence to recover in the Black Forest, a mountain range in southwest Germany, where he discovered a passion for the arts. He began taking pictures of the landscape with his camera.

Madvo enrolled himself into Le Conservatoire National de Musique de Paris in 1950 to study Opera and Opera Staging. There, he founded the Groupe Lyrique et Choreographique de l’Université de Paris and staged Christoph Willibald’s ‘Orfeo ed Euridice’ at the Sorbonne amphitheatre, an opera-ballet based on the Greek myth of Orpheus. Madvo continued to study the arts and enrolled himself as a student, yet again, at L’Institut des Hautes Étude Cinématographiques (IDHEC) in Paris. He trained in Movie Direction, Production, and Editing. As a student, Madvo directed his first film ‘La Petite Fille aux Allumettes’ (The Little Match Girl) based on the short story by Danish poet and author, Hans Christian Andersen.

Madvo graduated from IDHEC in 1956 and promptly worked as a Director in Movie Production for the UNRWA in Beirut. He worked there until 1960, whereafter he took a one-year paid absence to attend a course in movie production and direction of photography in Paris. He directed and photographed four documentary films as part of his diploma, such as: Fontaines de Paris (1961), Vitraux de Paris (1961), Paris: le Passé et le Présent (1961), and London at Christmas (1961). Madvo returned to the UNRWA to work as a Director and Cameraman in 1962.

Madvo moved to Saudi Arabia in 1965 and worked as a Consultant in Cinematography for Arabian American Oil Company (or Aramco), a state-owned oil company of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. He produced an average of one documentary film per week for the Aramco TV station. In 1968, Madvo migrated back to Lebanon as he directed and produced documentary films for Lebanon’s Ministry of Information. In the first half of 1969, Madvo worked as the cinematographer for ‘A Boy from Bahrain’ (1971), now renamed as ‘Hamad and the Pirates’ (1971) directed by Richard Lyotard: a two-hour feature about a young Bahrain boy who gets involved with pirates in the Persian Gulf. In the second half of 1969, Madvo directed, photographed, and produced ‘Liban Pays de Soleil’ for the Ministry of Tourism in Lebanon.

Note: Persian Gulf and Arabian Gulf are both appropriate terms to refer to the body of water between Iran and the Arabian Peninsula. ‘Persian Gulf’ has been used for centuries and dates back to the Persian Empire (present-day Iran). ‘Arabian Gulf’ is more recent in comparison, and is associated with the rise of Arab nationalism in the 1960s.

Madvo founded his own production company, World Film Productions, in 1970. He was finally able to use his artistic freedom and independent funding to make his own film, instead of working on a contract-basis that he did previously. It was during this time that Madvo directed, photographed, and produced Dispersés par le Vent (Blown by the Wind, 1971). It was officially selected for the Venice Film Festival, won awards at the Leipzig Film Festival, as well as in (then) Czechoslovakia and Tunis. However, Madvo’s happiness was short-lived as his wife tragically died from a car accident and left behind their two sons. Before the family migrated to Toronto, Canada, Madvo organized the Festival International du Film de l’Ensemble Francophone (FIFEF) in Beirut, 1973, and officially transferred his company to Canada in 1974.

From 1974 to 1983, Madvo directed and co-produced 19 half-hour documentaries about various countries for the series, Countries and People (Pays et Peuples) for the Ontario Educational Communications Authority (OECA; now TVOntario), under the producer Leopold Lacroix. The series briefly explored each country’s geography, history, sociology, ethnography, customs, traditions and cultures, such as: Kuwait, Jordan, Iraq, Lebanon, Iran, Israel, Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Morocco, Greece, Yugoslavia, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Brazil, Venezuela, Mexico, and the Vatican City. China, Japan, Vietnam and Thailand were filmed for their own documentaries, however were never completed and released. Madvo also made two independent documentary films about Canada: ‘Vivre en Paix’ (Living in Peace, 1974) of Canadian children’s paintings, and ‘Canada’ (1977) that highlighted each province’s tourist attractions.

Madvo quit working for the OECA in 1983. His first film after the departure was Arabs in Spain, a thirty-minute documentary that he directed, photographed, and edited.

Six-Day War of 1967

Before the Six-Day War, there were heightened tensions between Israel and its Arab neighbours. Palestinian guerilla groups in Syria, Lebanon and Jordan had been attacking Israel in 1966. In November 1966, Israel retaliated and struck Al-Samū: a village located in the Jordanian West Bank. In April 1967, the Israeli Air Force shot down 6 Syrian fighter jets. There were also (inaccurate) rumours that Israel planned on launching a campaign against Syria in May 1967. By the end of May, Egyptian president Nasser mobilized forces in the Sinai Peninsula, removed the UN Emergency Forces, closed shipped routes to Israel, and signed alliance pacts with Jordan and Iraq.

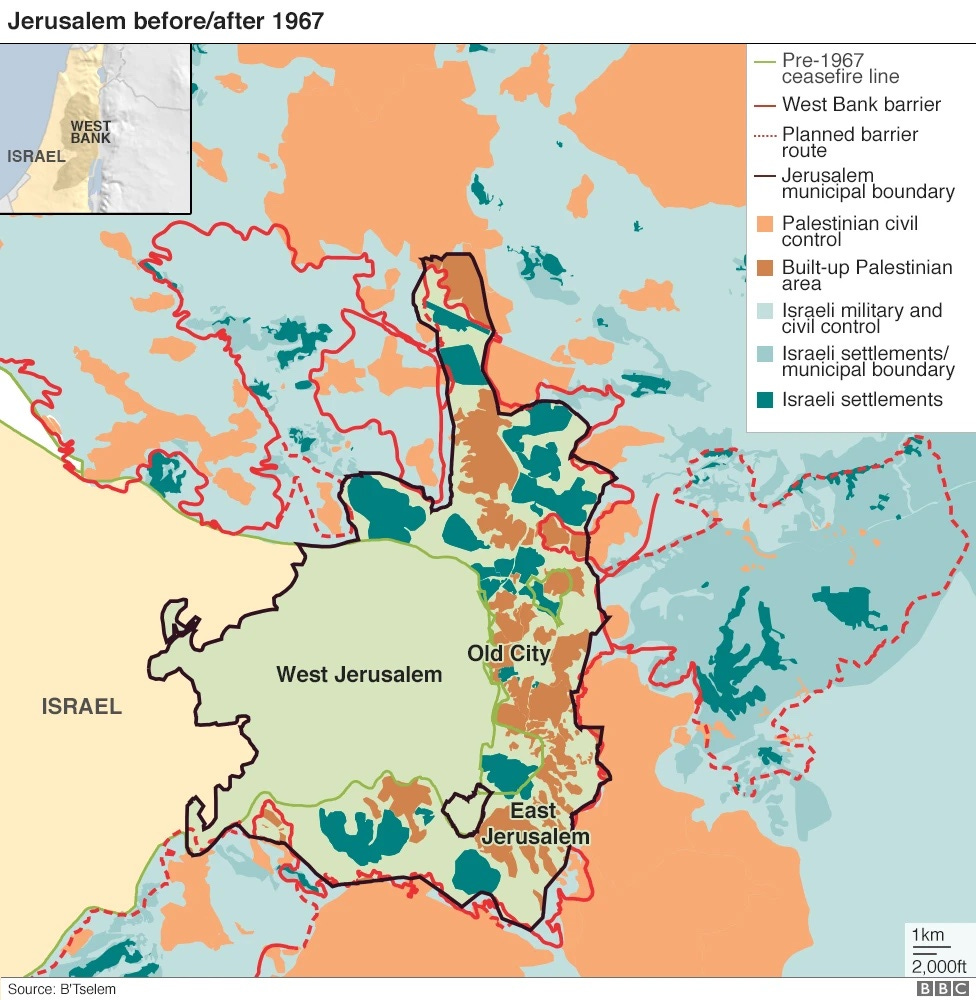

Israel launched preemptive air assaults on the Egyptian and Syrian air forces on 5 June 1967, before the Arab nations had a chance to mobilize. Jordan began to bomb West Jerusalem, and Israel’s counterattacks drove Jordanian forces out of East Jerusalem and most of the West Bank. The UN Security Council called for a ceasefire on 7 June 1967— immediately accepted between Israel and Jordan. Egypt accepted on 8 June 1967. Syria continued to fire shells from large guns in northern Israeli villages.

“Israeli aircraft were diving above our heads to terrorize us and make us leave… they fired their weapons at night to wreak havoc… We could see the tracer bullets like streaks of fire before us… they were firing on anything that moved, cars, and even livestock.”

— Fatima al-Ali, housewife from al-Asbah

During the last two days of the Six-Day War of 1967, Israeli engineer troops built access roads up Golan Heights to assault Syrians with armored vehicles and on foot. After the Six-Day War, Quneitra became occupied by Israeli military forces and Golan Heights was integrated into Israeli administration. 5 Arab villages in Golan Heights remained and were offered Israeli citizenship, but most declined and kept their Syrian citizenship. 30 Jewish settlements established in Golan Heights by late 1970s.

For Palestine, the war marked the start of a new phase in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, because it created hundreds of thousands of refugees and over 1 million Palestinian were forced into Israel’s occupied rule. Months after the war in November 1967, the UN passed Resolution 242 and called for Israel’s withdrawal from the territories it captured in exchanged for lasting peace.

In 1976, Israeli war hero and Defense Minister Moshe Dayan spoke to a journalist about the war, but his comments were not made public until 1997:

“I made a mistake in allowing the [Israeli] conquest of the Golan Heights. As Defense Minister I should have stopped it because the Syrians were not threatening us at the time… Of course, [war with Syria] was not necessary.”

— Moshe Dayan, 1976

He noted that he reluctantly gave the order to attack Syria, despite Syria already agreeing to the ceasefire in early June 1967.

Palestinian Agriculture

The history of Palestinian agriculture is one of the oldest agricultural settlements in the world, even dating back to 8000 BCE, as the Levant is considered to be one of the birthplaces of agriculture. Historically, the Levant region generally cultivated wheat, barley, rye, lentils, peas, and the oldest known evidence of the production of bread-like food was found in Shubayqa (located in northeast Jordan). The Palestinian region specifically grew Einkorn (another type of wheat), emmer wheat, barley, lentils, peas, chickpeas, bitter vetch, and flax during 8000 BCE. Scholars believe that the fig tree may have been domesticated earlier, around 9000 BCE, and the olive tree during 6000 BCE.

In modern times, rain-fed agriculture (“ba’ali”, referring to Canaanite God of Rain: Ba’al) continues to be a crucial part of Palestinian society, culture, and economy. It fuels their export economy while sustaining their own population needs. The 1950s and 1960s saw Palestine as famous for its citrus production and export, with 30-40% of the workforce employed in this industry. After the 1967 war, Palestinian agriculture started to shift towards producing strawberries and flowers, due to incentives from the Israeli government to meet their market needs. According to the Council for European Palestinian Relations in 2012, the agricultural sector formally employed 13.4% of the population and informally employed 90%.

However, the World Bank reported that Palestinian agriculture suffers from the land being razed for Israeli military and settler use, with the 1979 Likud Israeli government viewing local agriculture as a hindrance to its aim of annexing land. As a result, the Likud government reduced water quotas for farming and forced Palestinian farmers to seek day jobs in Israel. They sought to decrease Palestinian ownership of land in the West Bank by 40% within 6 years. The Israeli Minister of Agriculture at the time, Ariel Sharon, spearheaded the construction of Israeli settlements in the West Bank and Gaza Strip until the 1990s. Afterwards, Sharon became the Prime Minister of Israel and constructed the West Bank barrier.

“We had become skilled at finding our way in the darkest nights and gradually we built up the strength and endurance these kinds of operations required. [...] Ambushes and battles followed each other until they all seemed to run together.”

– Sharon, in his autobiography describing his participation in the 1948 Nakba (2001)

The sale of goods from Palestine to Israel became subject to licensing in 1984. Israel was not, and still is not, a commercial producer of olive products, so Palestine became a captive market on goods that Israel needed, yet was restricted on everything else. The final product was determined and controlled by Israeli policies. However, the means of production was also controlled; with an increasing number of settlers owning the land, many Palestinian farmers were sharecroppers. They cultivated the land that the Israeli settler now occupied, and had to split 50% of their crops with the Israeli landlord, meaning the farmers had less to sell in the end.

Agriculture in the Gaza Strip has been severely decimated since the 2023 genocide, due to intense Israeli bombing and attacks. In June 2024, the United Nations Satellite Imagery Agency (UNOSAT) stated that 57% of Gaza’s crop fields showed significant, and maybe permanent, declines in density and health. In October 2024, the UN Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) reported that 150 communities were isolated from their agricultural land by the West Bank barrier and unable to cross the 69 agricultural gates. Gaza used to be an important trading place and port city; now, it is a target for Israeli settlers to destroy linkages that Palestinians have to their land, traditional crops, and water sources.

Agriculture and Folklore: More Than “Just Land”

" لو يذكر الزيتون غارسه لصار الزيت دمعا ”

“If olive trees knew the hands that planted them, their oil would become tears.”

– Mahmoud Darwish, from his poem An Al Sumud (On Resiliency, 1964)

Agriculture in the Palestinian context is traditionally seen as much more than a mere source of income. For them, it is also an attachment to the ancestral land– agriculture represents a sense of belonging that is part and parcel to the Palestinian identity. Their oral history surrounding agriculture, such as the practices of cultivating olive trees, grains, fruits and vegetables, are deeply intertwined with the region’s history, culture, and traditions. Agriculture then serves as a central presence of Palestinian folklore.

Land and agriculture are associated with the term ‘sumoud’, which means ‘steadfastness’. It explains the rootedness of Palestinians to their land, and extends beyond the Western colonial concepts of modern nationhood and statehood. Sumoud identifies Palestinians as caretakers of the land, to the extent that their dignity and honour are tarnished if their land is taken away, especially if this is done so unlawfully.

The olive tree is a symbol for resilience and longevity. Traditional folklore says that the olive tree has “witnessed generations and empires come and go” as a metaphor for the enduring spirit of the Palestinian people (sumoud). The olive harvest in late autumn usually sees communities come together to harvest them together while singing ‘maqamat’ (traditional songs) of love, unity, and the land. In fact, the first rain after summer is an important seasonal marker, called ‘shatwat tishreen’ (شتوة تشرين), signaling a blessed time of abundance. As the harvest is a time of collaboration and celebration, it may also be accompanied by other folk practices like dancing and storytelling.

The olive tree is also seen as a symbol for peace, with various Abrahamic myths suggesting that it was the first tree planted by Adam and Eve, and the dove that flew back to Noah’s ark carried an olive branch in its beak. A chapter of the Quran (surah) is dedicated to the olive, with the surah an-nūr (chapter of light) alluding God’s light “as a lamp lit from a blessed olive tree, neither of the east or west, whose oil would almost glow even if untouched by fire”.

“One cannot ignore the presence of this time, nor its special scent– the aroma of fresh olives mixed with the scent of soil dampened by the first rain, and pots of sage tea cooked on bonfires in every home or plot.”

– Muzna Bishara, in her article for ASIF (2021)

Other harvests, such as wheat and barley, would similarly be celebrated with community prayers and practices. They would be planted and sung with prayers, community feasts, and songs as families and neighbours strengthen their social bonds. Agricultural myths and stories prophesied that the land would reward those who treated it with respect. Farmers would pray for good rains, and many Palestinian folk stories and proverbs stress the relationship between the land and its people. For example, they believe that “the earth speaks to those who listen”, meaning that those who respect and care for the land will be blessed with good crops and harvest.

For Palestinian farmers, maintaining the land is therefore an obligation and oath that they take to solidify their identity. Their agricultural practices are rooted in religious and cultural customs and rites. They are the caretakers of olive groves, fruit orchards, wheat fields, and terraced hills.

“In the same way that the trees can survive and have deep roots in their land, so, too, do the Palestinian people.”

– Sliman Mansour (co-founder of the League of Palestinian Artists), in an interview with Arab News (2021)

Evolution of Palestinian Music

“Oh wind, if you will, take me home (…) “Oh how I fear growing up in this exile, while my home never knows me.”

– Blown by the Wind (1971)

Palestinian music (الموسيقى الفلسطينية) is one of many regional subgenres of Arabic music, as heard throughout ‘Blown by the Wind’ (1971).

Before the 1948 Nakba, Palestinian music comprised a myriad of cultures, ethnic groups, and religions, such as the Arabs, Arab Christians, Druze, Muslim Bedouin, Jews, Samaritans, Circassians, Armenians, Doms, and more. Many lived in cities and rural areas as farmers or nomads, so it was difficult to distinguish Palestinian music from the wider Levant influences. Farmers (‘fellahin’) sang ‘ataaba’ folk songs for fishing, shepherding, harvesting, and making olive oil. There were also traveling storytellers and musicians called ‘zajaleen’, and weddings were home to distinctive celebratory music, including the ‘shaja’ and ‘dal’ona’ to dance the dabke. Most of these folk songs can still be heard today at cultural occasions.

At around the end of the 19th century, western Christian missionary schools were founded in Palestine, where Franciscan monks brought over western classical music and the practice of writing musical notation to the area. One of the first Palestinians to study music under the monks was Augustin Lama who later taught classical western music to other Palestinian musicians. Around this time, Radio Jerusalem became established in 1936 and played a critical role in fostering music production during the British Mandate in Palestine. It attracted musicians from Palestine and neighbouring Arab countries to broadcast and record their works on the radio. Radio programs ran three divisions: Hebrew, English, and Yahya al-Libabidi ran the Arab music division. He played songs from musicians like Rawhi al-Khammash, Mohamed Ghazi, Yahya al-Saudi, Riad al-Bandak, and himself. They all composed in the traditional Arab genre and based their lyrics on classical Arabic poetry: muwashsha and the taqtuqa.

After the 1948 Nakba, musicians gathered around the towns of Nazareth and Haifa to perform songs that surrounded new themes: statehood and Palestinian nationalism. Yusuf Batruni, Rima Nasser Tarazi and Amin Nasser composed according to Arab classical music and followed the styles from Cairo and Damascus, as Umm Kulthum and Sayed Darwish were popular Arab musicians at the time. They used the poems from Kamal Nasser for the lyrics.

A new kind of music emerged after the Six-Day War of 1967, when Israel occupied the rest of Palestine, called “committed songs”. Musicians fleeing from the war who became the diaspora, and musicians who stayed in Palestine, began to pivot towards a harder theme of resisting occupation and describing historic events. Popular artists at this time included Sabreen, Mustafa Al-Kurd, Al Ashiqeen, Zeinab Shaath, George Totari, and George Kirmiz.

Palestinian youth created a new music subgenre in the late 1990s– Palestinian rap and hip hop– which blended Arabic melodies with Western beats, with lyrics in Arabic, English, and sometimes Hebrew. Popular rap group, DAM, were the first musicians to do this. They were inspired after watching a music video from Tupac and later tailored the style to express their own grievances with the social and political climate they lived in. One of the biggest moments in modern history is when Mohammed Assaf won the Arab Idol competition in 2013. He earned one of the biggest voter turn-outs of all time from the Arab world. After his success on the show, he recorded ‘Ana Dame Falastine’ (My Blood is Palestinian) and became one of the highest selling Palestinian artists of all time.

“Spreading the words of young people and watching them achieve their dreams– this is much better than the sound of gunfire.”

– Mohammed Assaf, after his victory in Arab Idol (2013)

Thanks for reading our post reviewing Blown by the Wind (1971) by Jacques Madvo! All opinions stated in our review are held by Narratives of Resistance only– it does not represent the views of anyone else. If you have watched this film or came to one of our film festivals in 2024, leave a comment below or DM us for a chat! Please check out the hyperlinks if you want to learn more about the director Jacques Madvo, the Six-Day War of 1967, Palestinian agriculture, and about traditional Palestinian music.

Donate to the Million Tree Campaign here! Launched in 2001, they replant trees in Palestine to counteract Israel’s deliberate confiscation and destruction of land, and help to develop farmers’ abilities to manage their agricultural land.

If you want to stay updated with our art and cultural engagements, subscribe to our Substack and follow us on Instagram @nor.films – we post event announcements, share charities, and other helpful resources to stay critically educated on resistance art.

Watched the short on YouTube. Powerful stuff. I also read your review on No Other Land. This is such good documentation of the art and its surrounding material. Keep writing and keep these expressions alive!