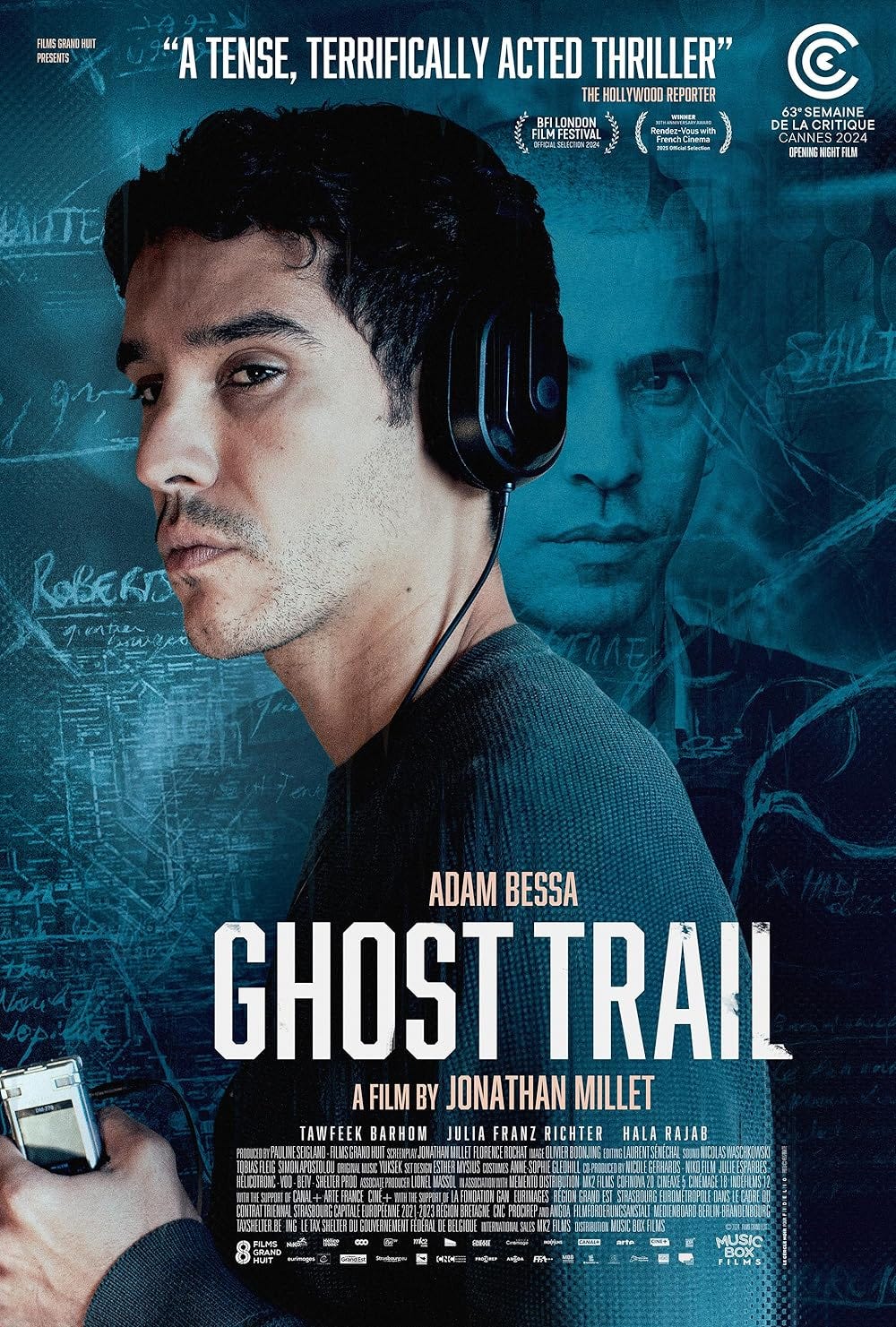

Review of 'Ghost Trail' (2024)

Our review of Ghost Trail (2024), Jonathan Millet's directorial debut of a feature film, with a brief discussion of Syrian literature, Sednaya prison, and ghraybe cookies.

4 out of 5 stars, crime-thriller, revenge, psychological

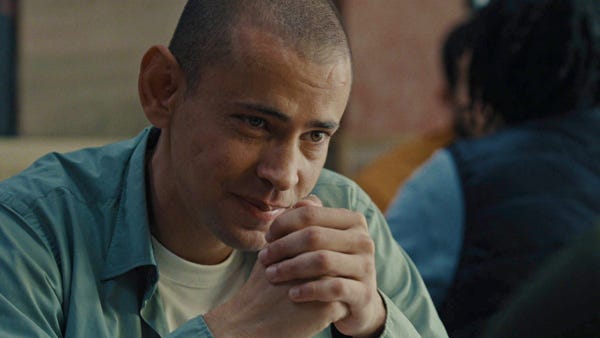

‘Ghost Trail’ (2024) is a nail-biting thriller that keeps the audience at the edge of their seats. Centred around espionage, the film leaves subtle clues for the audience to analyze throughout the viewing and shows a multifaceted nature of both the characters and the situations they find themselves in. The protagonist, Hamid Yakat (French-Tunisian Adam Bessa), lives a double-life as he searches for his torturer from Sednaya, Harfaz (Israeli-born Palestinian Tawfeek Barhom), who also escapes his past and lives a double-life. Throughout his journey, the film highlights sensory details like sight, sound, and smell to immerse the audience into Hamid’s intimate perspective as he fights against his body’s traumatic memories.

The film starts with a large group of blindfolded men crammed together in a moving truck. They are left in the middle of the desert heat in Syria, a sweltering temperature that the audience can physically feel through the glaring gaze of the sun, and the protagonist takes in his surroundings. It is unclear whether he can decipher his location as his blindfold is taken off. At the time of March 2014, the desert is bleak and empty. However, the protagonist finally looks ahead and follows his fellow men into the distance. The below photo is taken from TravelMag and is approximately similar to the desert scene shown in the film.

Two years later, in 2016, the protagonist works on a construction crew in Strasbourg. He gets called over by a fellow worker of whom the protagonist may want to talk to. The protagonist says that he is looking for his cousin named Sami Hanna, and shows a blurry photo taken from a CCTV screenshot. The worker he talks to shakes his head; he doesn’t know of a Sami Hanna from the refugee camp he was in. However, the protagonist is not too dejected. He carries on with his day with the composure of someone who has been rejected many times before.

The protagonist enters a refugee camp with hopes that Sami Hanna might be there. The camp is holding an open community event where other Arab people gather, share food, and collectively grieve their refugee status as a group. He meets this young woman, Yara (Syrian Hala Rajab), who serves food to an elderly man. He shows the same photo from before, yet Yara is suspicious of him. She mentions that due to the political strife in the region, she is wary of anyone who comes to these camps and searches for individuals with any possible ulterior motive. Are they informants? Are they regime dissidents? To Yara, these questions are none of her business. Either way, she doesn’t want to get involved.

To gain Yara’s trust, the protagonist names himself as Amir. He explains that he was a professor in Middle Eastern literature from the University of Aleppo, Syria, before he became displaced in Strasbourg. Yara squints and decides to test him. She begins to recite a famous modern Syrian poem, “Embroidery” by Saleh Diab. He continues:

What can we do

underneath a foreign sky

but listen to forgetfulness

as it embroiders our lives

like lace.

Yara decides to trust the protagonist and tells him to talk to her another day, when she would be more available to tend to their conversation.

The audience notices the start of mystery and espionage in a short scene when the protagonist sits on a park bench and asks for a book. Before this, the film leaves subtle clues about the plot: a friendless Syrian man in the middle of Strasbourg is looking for someone. The woman (Julia Franz Richter) sitting on the other end of the bench maintains the distance between them, yet they exchange a few knowing words. She leaves. The protagonist picks it up, the front cover reading ‘The Jasmine Scent of Damascus’ by Nizar Qabbani, and flips to a section detailing information about his target. He takes it and leaves.

He enters an immigration office and confesses his real name: Hamid Yakat. He tells the immigration officer that he wants to go to France to create a life for himself, and that he has fled from Sednaya Prison in Syria. The admin sighs and explains that ‘everyone says that to get their papers’, bemoaning how it is difficult to verify the validity of Hamid’s statement. Hamid immediately stands up, emotionless, and turns around to lift his shirt. The audience does not see the scars, but it is inferred from the shocked looks of horror from the immigration officer. The officer immediately searches for suitable job openings for Hamid in France and offers a position as a visiting Professor in Arab Literature in the University of Nancy.

Excited to share the news, Hamid uses a computer at an Internet cafe to video call his mother (Shafiqa El-Till). She resides in a refugee camp in Beirut, Lebanon, where she struggles to live comfortably on a daily basis. Hamid’s heart breaks for her yet he maintains his composure to free his mother from worrying about him. He lies about his well-being. Notably, he does not share his ambition to hunt down his torturer. She believes that he is in Berlin, Germany, with other Syrian refugees. His mother complains about her living conditions and immediately brushes them off. She has complete faith that her sacrifice allows her son to live affluently and to heal from the traumas in Sednaya.

“We haven’t had water in two days but what can you do? It won’t stop me from talking and seeing you.”

Hamid continues to search for his abuser and sees him on the street. He follows him into a university campus, convinced that it is him, it is Harfaz, the one who inflicted the scars all over his back. He does not, for a second, entertain the thought that time has eroded the memory of Harfaz’s voice and scent. Hamid sniffs the back of the suspect’s neck and steals a glance at his student card. Hassan al-Rammah– the same name of a Syrian chemist and engineer during the Mamluk Sultanate who studied gunpowders and explosives, and invented prototypes of warfare, like the first torpedo in 1250. He unwittingly follows the man’s seemingly normal life as a university student in chemistry, who has a girlfriend and goes on dates with her to a Christmas market. Hamid’s obsessed conviction leads him to the man’s apartment door where he spends the night with his date. He encodes the voice into his memory.

At a later date, Hamid asks Yara to accompany him to the same Christmas market to tail Hassan. They exchange normal conversation as refugees. They muse and fantasize about meeting under different circumstances, where they are not on the run from their home countries’ political tensions and fight for their survival:

Yara: I wish we had met in a different world.

Hamid: Different? What would you be doing?

Yara: I would be doing underground concerts in Damascus basements. You?

Hamid: I played guitar.

Yara: Guitar? See? You can be a normal guy.

Even in this brief exchange about their personal dreams and past lives, Hamid does not reveal much about himself. It is clear that despite both of them being refugees, their minds are still in different worlds– Hamid does not delve into his goals because his ambition of hunting down his abuser is concealed in secrecy. In contrast, Yara is open about her fantasies. Her little quip reveals that she is passionate about music and imagines herself as flourishing in the large city of Damascus, a cultural hub of the Middle East.

This quick escape of mundanity falls short as Hamid returns to the Internet cafe and reveals his findings to his group of spies. They play a war game as they question whether Hamid has truly found Harfaz, and strategize their next steps and countermeasures if he has not. They refer to each other with code names and emphasize that they must collect as much evidence against Harfaz as they can. One of them asks a profound question that clues the audience into the reason behind the group’s establishment and meticulous operations:

“Putin prevented others to act in Syria. Just one question: Can we still trust the international justice?”

However, Hamid is adamant that he has found him; he cannot forget the pitch and cadence of Harfaz’s voice, his scent, nor even his breath, as they are all etched into him with the scars on his back. He requests for audio recordings to confirm his suspicions.

The German woman meets Hamid again and hands over the tape recorder. The audience now understands that she is part of the spies group yet surprisingly, she reveals her real name to Hamid. Nina, she says, and insists that Hamid’s real name would stay confidential between them. He obliges. In a lonely spiel, Nina shares her motivations for joining the group of vigilantes: her husband was Syrian and was arrested in Sednaya, and she lost their son, Rael, in the conflict. She offers a glimpse of vulnerable humanity that sits alone behind the mask of revenge. Sympathetic, Hamid shares his own history. His wife, Lina, and his daughter, Maya, died in a bombing while he was imprisoned. They share a quiet moment of grief.

For the following few weeks, Hamid obsessively listens to the audio recordings on repeat. The clips are a compilation of fifty witness statements of their time in Sednaya prison, who recall burned bodies with holes, melted skin on arms, legs, and faces. The voices amalgamate into a chaotic chorus as gunshots and screams echo in the background. Hamid’s breath hitches. His fingers find his neck, rubbing, scratching, in meager attempts to ground himself back into reality. These nervous ticks recur even as Hamid travels to Lebanon to meet with an old regime deserter who worked with Harfaz. Was Hassan really Harfaz? Would this regime deserter be able to confirm it?

He follows his target to the university, and trails him again through his daily routine: the park during his morning run, university lectures, the library, and a local Lebanese restaurant. The restaurant is crowded and Hamid can’t find a place to sit. Hassan beckons him over and offers to share his table while Nina stares, panicked, in the corner. Spies are not supposed to get close to their target. Their target should not be able to identify members of the group. Hamid hesitantly sits down and humbly orders some ghraybe to eat.

This is arguably the most psychologically intense scene of the movie: Hamid and Hassan sit face-to-face and, through veiled conversation, both subtly attempt to verify each other’s identity as a regime supporter or as a regime dissident.

Hassan: I think I’ve seen you around.

Hassan: Did you go to the dunes? Lots of teachers took to the streets [to protest], even in Lebanon. That’s when the country falls.

Hassan: You can’t start a new life if you keep dwelling, dwelling, dwelling on the past. You have to move on.

Hassan: Syria… it’s over for us. Move on.

Despite Hassan’s composure, Hamid notices that Hassan’s hand trembles while he eats. He remembers that the audio recordings mentioned Harfaz having a nervous system condition. It convinces Hamid that the person sitting in front of him is indeed his torturer, the war criminal Harfaz. Hassan leads Hamid to a secluded courtyard within the university and shares some Syrian food as they sit in the scent of the jasmine flowers, noting that it tastes like home. It is an unexpectedly humanizing perspective of a war criminal. Hamid’s trauma runs deep as he freezes, awkwardly accepts the snack, and body steadies himself to flee at a moment’s notice.

The film’s penultimate scene shows Hamid burying photos of his wife and daughter in the ground as he lovingly says:

“Our teams will ease my grieving, but you will live in my memory forever.”

Hamid gives a large folder to a Parisian reporter from Le Journalisé du Monde. It contains many documents detailing Harfaz’s escape to Strasbourg, his new identity as Hassan, and evidence of his activities as a war criminal in Sednaya. The audience learns that Hamid has left the vigilante group; hunting down Harfaz was likely his only mission. He walks into a lecture hall and introduces himself as the visiting professor of Arab literature at the Université du Nancy. Hamid’s expression is sullen and empty as he scans the students’ faces. He is able to build a new life for himself in Europe but at what cost? Like the scars on his back, the traumas from Hamid’s past keep him trapped in Sednaya, a time when his mother suffered and his family bombed. With Harfaz under investigation, who is Hamid now?

Can Hamid move on?

Jonathan Millet

Jonathan Millet was born on 1 July 1985 in Paris, France. In an interview with Inside the Arthouse, Millet revealed that he knew he wanted to be a filmmaker since he was 8 years old. He always knew that he wanted to tell stories and his curiosity with visual narratives led him to filmmaking. However, he confessed that he did not watch many films during his childhood:

“I had no TV, and I was far removed from any theatre. So, each time I watched something visual, whether it be a commercial, a bad TV series or any film, it was a powerful experience because the lack of pictures makes any picture stronger. [...] I lived for almost a year and a half on a boat in the middle of the ocean with my father … and I had to wait until I was 17 before I had my own TV, and I was able to go out to the theatre.”

— Millet, in interview with Eye For Film (2025)

After studying philosophy, Millet spent three years alone filming remote regions as a reporter for image databases. This was his film school. He travelled to over fifty countries to make them accessible to Databank’s stock images, including: Iran, Sudan, Pakistan, all of South America, the Middle East, and extensively throughout Africa. During this time, Millet began to learn to curate an emotionally-laden atmosphere with just a few shots of faces and spaces, focussing on the tiniest of details in an otherwise ordinary setting. He spent a total of five years traveling, meeting people, listening to stories, and studying languages before he returned to France.

After this experience, Millet directed documentaries that explored themes of territory and solitude, such as ‘Ceuta, douce prison’ (2012), ‘Dernières Nouvelles des Étoiles’ (2017) filmed in Antarctica, and ‘La Disparition’ (2020) filmed in the Amazon. He has also directed six experimental short films that explore the human condition in challenging environments, like the César-nominated for Best Short Film ‘Et Toujours Nous Marcherons’ (2017) and ‘La Veillée’ (2017) which had a theatrical release. That same year, Millet was nominated as a “Talent in Short Films”.

Millet got inspired for ‘Ghost Trail’ after reading a short news piece: a simple three-liner about a group of Syrians intended to track down their country’s war criminals on the run throughout Europe. He explains that he is more interested in doubts and questions, rather than the truth, no matter what the truth turns out to be in the end. He likes the idea that reality is more complex than what the average person believes. With Middle Eastern geopolitics serving as the background context to the film, Millet reflected on his experiences solo-traveling as a young adult. Millet wanted to deliver the message that everything is complex, and time is needed to be sure about who someone is, and what is at stake for everyone involved. Many scenes in the film are based on first-hand accounts, yet these events receive little-to-no press nor media coverage. His mind stayed on the individual of whom the piece was centred upon and his imagination took over, believing that the lines between truth and fiction are blurred for the traumatized person.

The challenge during filming was to employ as few effects as possible, while relying on the language of film, where sound and editing are as important, if not more so, than the image. Millet worked closely with the cinematographer, Olivier Boonjing, to balance pure naturalism versus stylization that spy films needed to create suspense. In this way, the duo meticulously took takes that gave the editor (Laurent Sénéchal, who worked on ‘Anatomy of a Fall’, 2023) the freedom he needed. This included scaling the scene to crop shots, zoom in, stabilize or shake certain shots to evoke a specific effect or feeling to the viewer. To provide as much material as possible for editing, the crew also filmed a long 37-minute take where Bessa completely improvised Hamid’s daily life in his apartment, with the passage of time, solitude, moments of doubt, and tending to his wounds.

“What I like about trauma is, at first, it’s invisible. And you can use the tools of cinema to plunge deep into and access the mind of a character. This also explains why I chose cinema over another medium, because you can take this approach, and for me, that’s interesting.”

— Millet, in interview with Eye For Film (2025)

Millet is particularly interested in the intertwined aspects of loneliness and obsession in spy movies, such as the type seen in ‘The Conversation’ (1974) by Francis Ford Coppola. Even as a viewer himself, he loves thrillers, yet he believes that the anxiety is not enough to be worthy of the genre. Thriller films, Millet believes, must invite the viewer to decode the real-life story that the film seeks to tell. With espionage movies, Millet emphasizes that whatever the characters say is not necessarily the truth, so the viewer must think about the truth behind or beneath the words— or to even disregard the words all together, because the truth may lie in the character’s gestures instead. He took his 15 years of experience in making documentaries and short- to medium-length films to showcase a feature story of exile, bereavement, loneliness, but most of all, someone who has lost everything and wishes to return to a life worth living.

It should be noted here that Middle Eastern spy films are not usually portrayed from the angle of Syrian victims taking back their autonomy. Instead, they are usually depicted from an American viewpoint, like CIA operatives in: ‘Argo’ (2012), ‘Zero Dark Thirty’ (2012), ‘Syriana’ (2005), ‘Body of Lies’ (2008), and ‘The Good Shepherd’ (2006). Other spy films focus heavily on the Mossad, Israel’s intelligence agency, such as ‘The Angel’ (2018), ‘Munich’ (2005), and TV series like ‘Fauda’, ‘Tehran’, ‘The Spy’, and ‘The Little Drummer Girl’. Whether Millet was conscious of this fact or not, he adds a more nuanced layer to Arab perspectives and refugee cinema.

The casting process for ‘Ghost Trail’ (2024) was long, as it took over a year to cast Hamid and Harfaz. Millet absolutely needed a specific sense of authenticity, such as the Syrian Arabic accent that Bessa and Barhom were unfamiliar with, in order to properly achieve that perfect balance of realism and fiction. Thankfully, Rajab coached Bessa and Barhom on their accents. Millet also needed to consider the necessary safety precautions to reassure actors that if they accepted the role, neither they nor their families would experience any political repercussions. Thankfully, after auditioning over 140 candidates, Bessa was cast as Hamid. Millet explained that Bessa had the intensity he needed, such as the facial expressions of someone who survived imprisonment while losing his family, and convinced Millet that he knew how to give the audience access to this complex interiority.

“I must mention the very important role played by the Syrian actress Hala Rajab, who plays the role of Yara, who often advised us on the realism of situations and pronunciations. Among these, the scene of the revolutionary celebration, a sort of annual tradition that really exists in Syrian expatriate communities. This scene, which went on late into the long summer day, was a powerful memory, concluding with a series of sounds alone set to traditional songs sung by the extras at dusk. A poignant moment where reality and fiction are intimately intertwined.”

— Boonjing, in an interview with Association Française des directrices et directeurs de la photographie Cinématographique (2024)

Adam Bessa won Best Actor during the 9th Critics Awards for Arab Films on 17 May 2025, organized by the Arab Cinema Center, MAD Solutions, and International Emerging Film Talent Association. Other nominations for this ceremony included:

Best Feature Film – Ghost Trail

Best Director – Jonathan Millet

Best Actress – Hala Rajab

What’s next for Millet?

He is currently developing his second feature film, ‘Les Rêves Tempêtes’ (‘The Storm of Dreams’) in a similar manner as ‘Ghost Trails’. Millet will reunite with his producers from ‘Ghost Trail’, Lionel Massol and Pauline Seigland from Film Grand Huit, for another psychological thriller exploring the depths of human consciousness—- the life of the mind.

“Within that story, I want to feel the direction, the authorship, the sound, and all that. But first and foremost, I want the film to sweep viewers away. I don’t think cinema should be elitist or closed off. I believe we can make great auteur films that are accessible, films where everyone can find their own interpretation. It’s about making bold choices while keeping the film open to all.”

– Millet, in an interview with Variety (2025)

Literary References

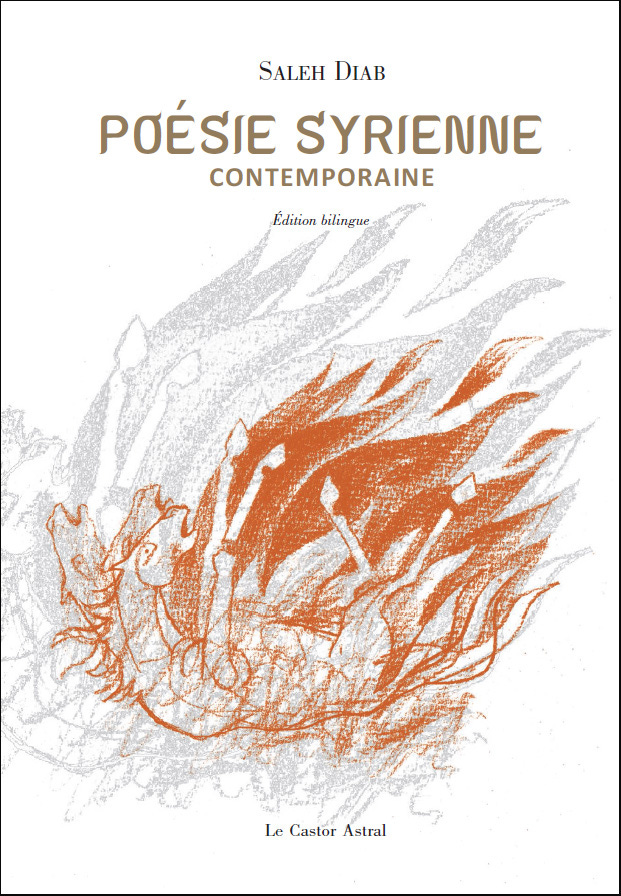

‘Embroidery’ by Saleh Diab

We have a country

where we left our friends

tangled together in sorrows

or picturing snow

hoping for the hilltops of their solitude to whitenWhat can we do

underneath a foreign sky

but listen to forgetfulness

as it embroiders our lives

like lace;

but regret adequately

in the open air

and dry up

reading books.— translated by Daniel Behar (2018)

Saleh Diab was born in Saint-Siméon le Stylite, near Aleppo, Syria in 1967. He was part of The Literary Form, a circle of poets that formed at the University of Aleppo in the 1980s and was crucial to Syrian modern literature. Members of The Literary Forum debated the various currents of Arabic poetry, developed the poetry of the spoken word, and experimented with new poetic sensibilities that contrast with the traditional tafilah (تفعيلة), such as free poetry. Tafilah is a basic unit of meter or unit of rhythm within a verse, where the number and arrangement of tafilahs determine the meter of the poem. It was developed by Al-Khalil bin Ahmed Al-Farahidi’s system, ‘Al Arud’, where he identifies ten primary tafilah patterns used to construct the ‘Al Buhur’ (poetic meters).

After university, Diab lived in Beirut, Lebanon as a journalist and literary critic for four major newspapers from 1995 to 2000, such as: An Nahar, al-Hayat, Nidaal Watan, and Assafir. Afterwards, Diab moved to France and began pursuing his own writing endeavours.

Diab delved more into poetry– he translated and anthologized many French poets into Arabic, such as James Sacré, Jean-Yves Masson, Jacqueline Risset, Annie Salager, Marie-Claire Bancquart, etc., as well as translated Arab poets into French. He wrote two articles studying women poets: Récipient de Douleur (2007) and Le Désert Voilé (2009). Further, Diab has a doctorate in contemporary Arabic poetry from the University of Paris-VIII and has collaborated with many French language journals, like Autre Sud, Résonance Générale, Lieux d’être, NUNC, and Le Journal des Poètes.

His own poems focus primarily on free poetry and especially the prose poem. His poem collections include:

A Dry Moon Watches Over My Life (1998)

Greek Summer (2006)

You Go for Me with a Knife, I Go for You with a Dagger (2009)

I Went Through My Life (J’ai visité ma vie, 2013)

Diab’s latest book is an anthology of modern Syrian poetry, titled Contemporary Syrian Poetry (Poésie Syrienne Contemporaine, 2018). He believes that Syrian poets discovered new poetic styles in Arab poetry, such as the work of Adonis, Muhammad al-Maghut, and Nizar Qabbani. However, Diab equally believes that Syrian poetry was largely influenced by its neighbouring countries of Lebanon, Iraq, and Egypt, therefore his anthology paints an all-inclusive picture of Arabic poetry.

“In the face of human savagery and the collapse of all moral values, the pathetic role changes between victims and executors, martyrs and mercenaries, the widespread organized barbarities, [...] I wanted to present these Arab aesthetic achievements through their Syrian example, and its human depth in defiance of the proliferation of greedy political propagandists and blood merchants in the media [who present] shallow kitsch as great Syrian literature. I wanted to convey to French readers a voice other than the fake voice spread by politicians, NGOs, and certain political parties. The other voice which is being purposely erased, and which I celebrate, is the real Syrian poetic voice. It is the face of Syrians and their name.”

– Diab, in an interview with Arab Lit Quarterly (2018)

‘The Jasmine Scent of Damascus’ by Nizar Qabbani

Nizar Qabbani was born in Damascus in 1923 as the son of a middle-class merchant father. At the age of 15, Qabbani lost his sister to suicide– she refused to marry a man of whom she did not love– and this had a profound effect on him. Qabbani dedicated himself to campaigning for gender equality and wrote against male chauvinism to the extent that his work is often seen as a homage to womanhood. He obtained a law degree from the University of Damascus in 1945. As a student, Qabbani dabbled with poetry and published his first collection of poems in 1944 at his own expense: an erotic perspective of love told from a woman, called ‘The Brunette Told Me’. As a man in Arab society, this was scandalous, however a leading politician and family friend in the education department deemed it as acceptable and allowed the collection to be published.

“Love in the Arab world is like a prisoner, and I want to set [it] free. I want to free the Arab soul, sense, and body with my poetry. The relationships between men and women in our society are not healthy.”

– Qabbani, quote from Oshana

After university, Qabbani worked as a diplomat for the Syrian Foreign Ministry and lived in many cities, like Beirut, Istanbul, Cairo, Madrid, London, and parts of China until he resigned in 1966. Despite his travels, Qabbani’s hometown continued to be his muse. He described it in his will as “the womb that taught me poetry, taught me creativity, and granted me the alphabet of Jasmine.”

A Damascene moon travels through my blood

Nightingales… and grain… and domes

from Damascus, jasmine begins its whiteness

and fragrances perfume themselves with her scent

from Damascus, water begins… for wherever

you lean your head, a stream flows

and poetry is a sparrow spreading its wings

over Sham… and a poet is a voyager.– Qabbani, from his poem ‘Damascene Moon’

Qabbani wrote during a period of great political change and uncertainties in the Arab world, especially the Six-Day War of 1967, and often spoke out against western colonialism and the corruption of Arab leaders. He soon published a poem called ‘Marginal Notes on the Book of Defeat’, an open attack on Arab strengths and capabilities, which drew widespread multi-party criticism. As a result, the anti-authoritarian poem was banned in several countries, where he became exiled and lived in London until his death on 30 April 1988.

Living in the safety of London, Qabbani became known for his lyrical beauty, emotional depth, and unflinching exploration of love, loss, exile, and the complexities of Arab identity. His poems are characterized by their direct and accessible language, often employing a conversational tone that speaks directly to the reader. He established a publishing house in London where he continued to write both political prose and poetry, and continued to write for Arab newspapers like al-Hayat. Qabbani expressed his sorrow towards the political state of the Arab world and criticized those he felt were responsible. After his wife was killed by a guerilla bomb in Beirut during the Lebanese Civil War, he immortalized her by using her death as a symbol for other deaths of Arab people in the Levant by their governments:

Balqees, I ask for forgiveness.

Maybe your life was for mine, a sacrifice,

indeed I know well that your killers’ aims were to kill

my words!— Qabbani, in his poem ‘Balqees’

Sednaya Prison

Sednaya, also known as the Saydnaya Military Prison, is located 30 km north of Damascus, Syria. It is under the jurisdiction of the Minister of Defence and operated by the Military Police, notorious for the use of torture and excessive force. It was established in 1978 and consists of two buildings: one painted white for crimes and misdemeanours, like murder, theft, corruption and draft evasion; the building painted red held security detainees “on the pretext of opinions they expressed, their political activities, or fabricated allegation of terrorism”.

The Assad regime arguably increased political detention after the Arab Spring protests in 2011, also known as the Syrian uprising and Syrian civil war. Protesters initially demanded political reforms and an end to the Assad family’s autocratic rule, however the Syrian government responded with violent repression, mass arrests, and firing at protesters. As the conflict progressed, so did the sectarian divisions. Organized rebel militias regularly engaged in combat with government troops by September 2011. By this time, international parties like the United Nations and Arab League became involved and brokered a partial ceasefire. Approximately 600,000 Syrians have been killed in this civil war and 6 million have fled into exile.

The prison has long been synonymous with the horrors of the Assad regime as it became a primary site for detentions, torture and executions. They occurred regularly, usually on Mondays and Wednesdays, through mass hangings in the red building’s basement after sham trials lasting no more than three minutes. Many survivors reported systematic daily beatings, sub-human conditions, degrading treatment, as well as other prisoners dying on a daily basis. Many were denied food and water for prolonged periods. Guards ruthlessly enforced a rule of absolute silence.

“The physical pain they put you through is miserable, from the bones that are being broken to the nails that have been pulled out. But more than that, the physical pain is something you sometimes get used to. But there’s the mental suffering they put you through.

Imagine when you sit in your room with your cellmates, and the guard comes. And with his very soft voice, he tells you, you have to choose one of you to be executed tomorrow. If you don’t choose one of you, I will choose three of you to die. Then he leaves. And then you have to sit with your cellmates, and you have to ask them the question– who wants to be murdered brutally tomorrow? Who wants to volunteer to never see their family again?

It’s been a place of hopelessness, helplessness. It’s been a place that reminded us that the world doesn’t care. The world knows, but the world doesn’t care. The world is doing nothing. And when you believe no one cares about you, no one is doing anything to save you, you give up.”

– Alshogre, Sednaya survivor in an interview with NPR (2024)

“They had plastic bags full of faeces and urine because people weren’t able to go to the bathroom– if they were allowed to go to a handful of toilets here, they were only given a few seconds, so they were relieving themselves and dumping the plastic bags in the corner of the cells.”

– Yalda Hakim, reporter on Sky News (2024)

Ghraybe (غريبة)

Ghraybe (غريبة), also known as ghraybeh, ghorayeba, ghoriba, ghribia, ghraïba, gurabija, ghriyyaba, kurabiye, or kourabiedes, is a shortbread-type biscuit, usually made with ground almonds. The different spellings and pronunciations vary with the region, and are found in most Arab, Balkan and Ottoman cuisines.

The earliest Arab cookbook details the recipe for a shortbread cookie similar to ghraybe, but without almonds, in the 10th century Kitab al-Tabīh. The linguist Sevan Nişanyan wrote in his 2009 book of Turkish etymology that ġurayb or ğarĩb has an Arabic origin, meaning exotic. However, his 2019 online dictionary now specifies that the earliest known recorded use of the word was in the late 17th century, with an origin from the Persian gulābiya (cookie made with rose water), from gulāb, related to flowers.

Ghraybe can translate to ‘melt’ or ‘swoon’ in Arabic, which aptly describes the delicate, buttery and crumbly texture of the ghee-based biscuits. Some Levant variations may include ground almonds, pistachios, and rose water for added texture and taste. They are popular treats to snack on during the holidays, such as Ramadan and Eid, or even simply enjoyed with coffee and tea.

Thanks for reading our post reviewing Ghost Trail (2024) directed by Jonathan Millet! All opinion stated in our review are held by Narratives of Resistance only– it does not represent the views of anyone else. If you have watched this film, leave a comment below or DM us for a chat! Please check out the hyperlinks if you want to learn more about Jonathan Millet, the film’s references to contemporary Syrian literature through Saleh Diab and Nizar Qabbani, Sednaya prison, and ghraybe.

If you want to stay updated with our art and cultural engagements, subscribe to our Substack and follow us on Instagram @nor.films – we post event announcements, share charities, and other helpful resources to stay critically educated on resistance art.

very well written - I really enjoyed the way the film's plot was described in the beginning and then exploring its allegories and the context it rests on. What made you focus on the biscuits at the end? Any significance there you think? They sound delicious; I have to find them. Keep writing and sharing these films often unnoticed by dominant media!

This film looks amazing! Do you have any information about how to access it! It doesn’t seem to be available on any streaming service I have access to.