Review of 'To A Land Unknown' (2024)

Our review of To A Land Unknown (2024), Fleifel’s directorial debut of a feature film, with a discussion of displacement, Greece's stance on refugees, and interview with producer Geoff Arbourne.

4.5 out of 5 stars, crime-thriller

‘To A Land Unknown’ is an incredible thriller that delivers both a humane, yet harrowing story of Palestinian refugees in Greece, who swindle innocent individuals for their own personal gain. For once, this movie about refugees does not explore the plight of leaving the country they came from, nor does it paint the main characters as heroes. It is not the typical inspiring movie about refugees. Instead, their refugee status sits in the background to provide context for the story without taking the centreplace. The story is complex and strife with nuanced areas with morally grey characters, and the audience is forced to understand why the main characters commit their crimes while equally acknowledging that those crimes are horrible.

“I try to be honest with the human experience.

Human beings are not perfect. We’re not always pure.”

— Mahdi Fleifel, to The New Arab (2024)

The film starts with an audio of a loud train speeding through gusts of wind, playing over short and disoriented old film strips of the main characters, Chatila (Mahmoud Bakri) and Reda (Aram Sabbah). The audience is left to assume that Chatila and Reda fled Palestine in a tumultuous journey given the roaring engine and harsh winds. They smoke cigarettes on top of a mountain hill and the camera shows glimpses of the Athenian scenery below. The film strips end and a quote from Palestinian academic, Edward Said, appears across a black screen:

“In a way, it’s a sort of fate of Palestinians not to end up where they started, but somewhere unexpected and far away.”

— Edward Said (1998), In Search of Palestine, Edward Said’s Return Home

These words were cutting when they were first spoken years ago, when Benjamin Netayanhu was first elected as the Israeli Prime Minister and fears were prevalent regarding the recently-established Oslo Accords in 1993. Accompanied by the Gaza genocide of 2023, Fleifel’s choice to remind the audience of these words in his own feature film about refugees resonate even harder as we witness mass displacement and annexation.

After the quote fades away, Palestinian cousins Chatila and Reda sit on a park bench during a lazy afternoon in Athens. However, this setting is juxtaposed by their body language: they sit like hawks and scan the area, looking for someone to smuggle from. They notice a young Palestinian boy loitering around the park and chuckle to themselves as they estimate that the young boy was not settled and had only arrived earlier that day. Chatila eventually finds a target: a middle-aged woman as she walks past them. He nods over to her direction and Reda skateboards over, falls, and creates a distraction as Chatila runs over to steal her purse. They parkour through a labyrinth of alleys before stopping by a corner and scavenge their findings, only to discover that the woman only held 5 euros in her wallet. Chatila curses at the meager amount and Reda looks uneasy, asking, “What if she needs it for medicine”? This is the first time the audience is shown the difference between the two main characters: Reda is more humanistic and caring for others, while Chatila is more concerned about his own survival and uses others as a means to an end.

The young boy from earlier finds them and reveals that he witnessed the whole smuggling ordeal from the park. He introduces himself as Malik (Mohammad Alsurafa) and asks for help and a place to stay. Chatila, sticking true to his self-preserving nature, immediately refuses and tells Malik to go to the police station. Malik seems reluctant; how could he seek help from authorities when he was an undocumented displaced person? Would the police send him back to Palestine? Reda convinces Chatila to allow Malik to stay with them for a couple of days, and he sighs before bringing Malik to their neighbourhood.

Their neighbourhood is woven through another network of alleys. The refugee inhabitants play basketball at a makeshift court, blast music, and speak loudly to each other in Arabic. The camera follows closely behind as Chatila cautions Malik from speaking to anyone, and in a timely manner, a group of young men smoking around an improvised pit teases Reda, who stands uncomfortably. Chatila warns Malik to especially stay away from Abu Love (Mouataz Alshaltouh), the principal bully of the group, because he was bad news and alludes to Abu Love’s enabling of Reda’s vices. The three walk through an interconnected web of bedrooms packed with bunk-beds, tiny kitchens and dining tables amongst an overtone of lively chatters and conversations. The living quality of this centre is in no way abysmal, but it is also certainly not an environment to yearn for. It is overcrowded and lacks the quiet luxury of privacy.

The three end at a bedroom where single-beds and mattresses cramp together at a corner. It is Chatila and Reda’s corner, their own designated space in the thick of the larger quagmire. Malik situates himself in a barren bed, too stiff to look comfortable, and answers Reda’s questions about himself. Malik is stopping by Athens en route to his final destination in Italy to reunite with his aunt, who has also fled there, undocumented. Uninterested, Chatila calls his wife, Nabila, and asks about his two-year-old son. Nabila complains to Chatila’s tired ears about the refugee camp in Lebanon and wishes to leave soon. Chatila knows all too well that he must make as much money as possible to provide for his family and to help them quickly leave the Lebanese camp. What does emotionally strike Chatila, however, was hearing about his son’s wishes and subsequent disappointment of being unable to spend his birthday with his father. Disgruntled, Chatila cuts the call short after providing some more reassurance to his wife, and leaves to another unknown alley.

He deposits some cash and counts the amount he has saved in an envelope stashed in a nearby hiding spot before meeting with a human trafficker, Marwan (Munther Reyahneh). Marwan sighs and tells the desperate Chatila that he is experiencing difficulties in making fake passports for the cousins, explaining through his puffs of smoke that it is difficult to find people who look similar to them. However, Marwan sandwiches his frustrations with a promise that he will eventually bring Chatila and Reda to their own final destination in Germany— for a price. Marwan bemoans the expenses but his lack of sincerity is clear. After all, his body language is relaxed and his living quarters are decorated much more lavishly than what we have previously seen in the refugee neighbourhood, which was devoid of leisurely possessions and jam-packed with the dispossessed people’s bare necessities. Marwan wants more money but who was Chatila to complain? As a displaced person with almost zero connections, Chatila was shackled to Marwan’s unguaranteed service, much like a slave’s subservience to their owner’s unreliable mercy.

Discontent with the realization of needing to hustle more money, Chatila nabs a slice of cake and returns to the park at night. He brings it up to his face and smiles, eyes empty of joy yet lips spread wide, as he takes a picture and sends it to his son. A local Athenian woman laughs at him as she sits at a bench at the side. She drunkenly giggles as she holds her can of beer and confesses that she often sees him at this park during the day. Chatila responds by offering the slice of cake to her and explains that he doesn’t eat sweets and simply took the photo for his son to see. Thankful, the woman accepts the cake and introduces herself as Tatiana (Angeliki Papoulia). They acquaint themselves with each other and the audience sees a rare glimpse of Chatila with a lighthearted demeanour. It is a stark contrast to how he has acted so far, with a frown and a quick reflex to chastise Reda, whose only crime was behaving kindly to others. In another world where Chatila is not forced to scheme for survival, he is able to crack jokes and smile.

Chatila goes back to the hidden envelope after a few hours and finds that a sum is missing. He panics but knows who the culprit is. Sprinting back home, he goes on a rampage as he shouts for Reda in the uncharacteristically quiet neighbourhood in the early morning. Everyone is either sleeping or groggily waking up. Chatila pounds on the locked bathroom door and knocks it down amidst the complaints of his fellow inhabitants, telling him to keep quiet and not to cause a commotion. He finds an unresponsive Reda sitting on the toilet seat and realizes that he had relapsed after staying clean for one month. In a rehearsed series of actions signaling that Chatila has done this too many times before, he swiftly sobers up Reda in the bathroom before dragging him outside.

They argue in the middle of the courtyard. Chatila scolds Reda and asks how he could betray him by stealing the money, and even how he could betray himself in his journey to sobriety. The audience finds out later that Chatila’s words are not just laced with shock, but also fears of Reda betraying their dreams once they were to arrive in Germany. Alluded throughout different conversations in the movie, Chatila and Reda wish to open up a café and recreate the one that Chatila’s father used to run in Palestine. Their plan is for Chatila to run the operations with a fancy office and desk at the back, his wife Nabila as the chef, and Reda to greet the customers with a big smile while doing miscellaneous work. Reda desperately tries to appease Chatila and to placate his anger.

Reda: “I’ll get the money for you and go back to camp!”

Chatila: “You know what they say about you? You’ll deal that shit to the kids.”

Chatila storms off as a wounded Reda skateboards into another park. The camera zooms out and Reda’s figure gets lost behind the bushes—- it is clear that he is not just lost in the context of geographical displacement, but also emotionally feeling lost in the grand scheme of life. Reda escapes from his present reality as a refugee by using hard drugs and he also escapes from his own individuality as he disregards his own personal boundaries to pacify Chatila. He sells himself to a local man for a mere €30. At the same time, the scene cuts to a shot zooming into Chatila’s face. He reflects upon his words and realizes that he went too far during their argument.

Reda reappears at the front door and asks if Chatila could search within his heart for sympathy; he needs a roof to stay under as the drugs wear off. He cocoons himself with his duvet as he shivers uncontrollably. He grabs Chatila’s arm and delivers Chekov’s gun:

“I don’t want to die here.”

The plot picks up when Chatila hatches a plan to make money quickly: create a passport for Malik, find a local woman to pretend to be his mother, and fly them off to Italy. In return, Malik’s aunt would send thousands to Chatila’s account. It is almost scary as Chatila feigns a genuine-looking smile and charismatically reassures Malik’s aunt that the plan was trustworthy and guarantees that he is a reliable figure in this situation. At night, he stalks out Tatiana and follows her into a grocery store— she picks up a couple of bottles of beer and he offers to chivalrously pay for her. He is flirting. He knows that he can be charming. Tatiana, however, confronts him about his family back in Lebanon, to which he lies:

“I have no feelings for them– they are far away.”

They have sex the following few days and Chatila makes himself at home in her quiet flat, a clear luxury that he is not afforded back in his refugee-populated neighbourhood. He proposes the plan to her as she eats the Palestinian breakfast he cooked, and emphasizes how he is helping Malik out of good will. A glint appears in Tatiana’s eyes and she catches him in his lies. Chatila confesses the amount that Malik’s aunt will send him, and she demands a cut. Seeing no other choice, he agrees. They swiftly prepare the documents while Tatiana fights with herself as she realizes that this is human trafficking. Sure, she is on the whimsical side of life and is not the most straight-edged person, but she is still about to commit a crime. There is a poignant moment where Nabila calls Chatila as he brushes his teeth in Tatiana’s bathroom. The camera zooms into the mirror as he lets his phone ring.

Tatiana and Malik descend underground with their small suitcases to catch the train to Italy. They promise to call Chatila once they’ve safely arrived and have passed through Italian immigration– Chatila and Reda wait by the phone for the following few days. Chatila rings both Tatiana and Malik’s numbers incessantly to no avail. An Italian voicemail automatically plays. Sitting in the courtyard, Chatila lists out the potential scenarios that Tatiana and Malik have gotten themselves into, from being free to both being detained. The audience knows the answer. Chatila knows the answer. Reda, being his optimistic self, smiles and muses:

“So he’s in Italy with his aunt.”

However, Chatila is not satisfied. He still needs money for him and Reda to go to Germany, and to get his own family out of the Lebanese camp. He hatches a plan to kidnap other refugees who wish to flee to Italy, and to keep them captive in Tatiana’s now-empty flat until enough money is transferred to his account. He rallies Abu Love, Yasser, and a hesitant Reda. Chatila doesn’t care that he endangered Tatiana and young Malik; he is already on the hunt for the next scheme. A harrowing moment occurs when one of the refugees shows a photo of his daughter to Chatila, but Chatila remains silent with his jaw locked in place— in what is supposed to be a bonding moment of vulnerability, the scene is instead disturbingly eerie. The audience once again sees how Chatila is able to compromise his morality in order to achieve his goals.

In the middle of the operation, Abu Love recites an excerpt from Mahmoud Darwish’s epic poem of resistance, ‘Praise of the High Shadow’. In a middle of a drug-induced clarity, Abu Love demonstrates his love for literature and appropriately quotes the refrains for ‘The Mask Has Fallen’, and turns the scene into a meta-commentary of using other people in the name of resistance. His performance in this scene hints at his life before he became a drug dealer: sharp, educated and creative. Darwish’s poem itself is a prophetic warning when people do not take care of each other, as allies to join against a common oppressor, and instead if people prioritize their individual survival— leading to the tragic fall of everyone. Abu Love’s idle intonation delivers a satirical forewarning of the duo’s imminent futures.

Meanwhile, Chatila calls Nabila. Finally, the audience sees the cracks in his fortified exterior as he breaks down and comes to terms with reality:

“My love, do you know how we live here? We hustle people, we steal, we’re like animals. Worse than animals. We’re criminals, Nabila.”

Reda, despite doing his best to feed the kidnapped victims and to treat them kindly, is wracked by guilt. He takes the opportune moment of the quiet, early morning hours, and sneaks into Abu Love’s stash of cocaine while everybody else is asleep. When Chatila finds him, he immediately carries him out and hails down an off-duty bus driver, pleading to be driven to the hospital.

The bus passes through a tunnel and the dark screen forces the audience to reflect on the true land unknown. Was it the foreign lands of Greece, Italy and Germany? Was it a reference to how being displaced would change one’s character? Or, hauntingly, was the true land unknown something more spiritual, as Reda throws away the prospect of a new life because they achieved it through dishonest means? Although they have had their fights, Chatila and Reda truly loved each other as Chatila cries, kissing Reda’s face, as he talks about their dream in Germany:

“Do you think that café is just for me and Nabila? Like I’ve always said, when the customers walk in, the first thing they see should be your face. Your big, stupid smile will be there to greet the customers.”

Mahdi Fleifel

Born in Dubai in 1979, Mahdi Fleifel is a Palestinian-descent filmmaker who works between Denmark, England, and Greece. He spent his early childhood in the Ein el-Hilweh camp in Lebanon, and in 1988, lived in a suburban neighbourhood of Elsinore in Denmark, where he eventually naturalized. His parents were also born in Ein el-Hilweh and the family was forged by three generations of statelessness. In 2009, he graduated from the National Film and Television School at Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire. In 2010, he founded Nakba FilmWorks, a production company based in London.

Ein el-Hilweh (عين الحلوة), also spelled as Ain al-Hilweh or Ayn al-Hilweh, is the largest Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon and is home to over 100,000 residents. Translated to ‘sweet natural spring’, the camp was established in 1948 by the International Committee of the Red Cross to accommodate Palestinian refugees who were displaced by the Nakba. Since the Lebanese government nor the Lebanese Armed Forces are forbidden from entering the camp, it is believed that those fleeing from the government after the civil war take refuge in the camp. It is located in south Lebanon near the city of Saida, and is spread across private properties owned by villagers from Miye ou Miye, Darb es Sim, and Sidon. Due to its overcrowding, residents face difficulties such as severe poverty, unemployment, violence, and disrupted education among its youth population. The camp’s electricity and water networks are damaged in certain neighbourhoods, and some other neighbourhoods are split into political factions.

The duration of Fleifel’s stay in Ein el-Hilweh included the 1982 Lebanon War, where Israel invaded south Lebanon on 6 June 1982. Their invasion followed a series of attacks between the Israeli military (IDF) and parts of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) that operated in the area. The Israeli military sought to end Palestinian attacks from Lebanon, destroy the PLO in the country, and to install a pro-Israel Maronite Christian government. The IDF Chief of Staff Rafael Eitan noted that the invasion was “a war for Eretz Israel” — a war to consolidate the Israeli hold on ‘Judea’ and ‘Samaria’, a war to destroy any organized and cohesive expression of Palestinian nationalism.

“We did in Beirut exactly what [the Israelis] are doing in Gaza. We turned off the water, the electricity, everything.”

— Dr Ahron Bregman, King’s College London who served as an Israeli soldier during the 1982 conflict

The city of Sidon was subject to heavy aerial bombing and heavy casualties among civilians. Palestinian defence in the camp was heavily fortified, full of bunkers and many 13- or 14-year-old boys equipped fire positions like the rocket-propelled grenade (RPGs). Although the conflict ended only three months later, most Israeli forces settled in areas surrounding Beirut until they finally withdrew on 5 June 1985.

The 1982 Lebanon war also took place in the middle of the Lebanese Civil War, a 15-year conflict from 1975 to 1990. The state’s institutions deteriorated and military groups provided security when the government could not. Syria also intervened at the request of President Suleiman Frenjieh, however this sparked increased involvement from Israel, who armed and financed Christian militias in Lebanon because they considered those forces as allies against the PLO. Fueled by continued foreign intervention, Lebanese society from 1985 to 1989 descended into a militia economy, and political factions in refugee camps devolved into a ‘War of the Camps’. It was a struggle for control over West Beirut, and was considered as a sub-conflict between Syria and the PLO.

Lebanon as a country faced high unemployment, brain drain, and scarcity of goods and services. On the other hand, the military provided wages and rationed goods, services and wealth to their fighters. In 1987, the Lebanese pound fell— signalling a period of profound economic inflation. Delivery of UNRWA humanitarian aid to refugee camps became severely restricted and no fresh food nor medicine was allowed for over eight weeks. Violence escalated in West Beirut during the ‘War of the Flag’, Lebanese militia groups continued to clash with Syrian interventionist forces, and small Palestinian camps were destroyed and set on fire. Thousands of Palestinians fled to Sidon because it was not under the Lebanese Amal Movement’s control.

At the end of the war, an official Lebanese government report stated that around 2000 Palestinians were killed in inter-factional clashes between pro-Syrian and pro-Arafat oragnizations, however the real number is most likely higher because thousands of Palestinian refugees were not registered. Blockades meant that officials could not access the camps, and all casualties could not be counted.

“I don’t see myself as a political film-maker. I’m a storyteller. And I tell stories about exiles. I’m not an activist. I’m not a politician. I happen to be an exile from Palestine. People are waking up to the fact that we were robbed in broad daylight. There’s an ugly injustice going on, and, obviously, people want to know more.

It’s a challenge to tell our stories, because there are forces that don’t want these stories to exist. They want to erase them. They want to make us invisible. But we are here.”

— Mahdi Fleifel, to The Irish Times (2025)

Fleifel first experimented with film-making when he made return visits to the Lebanese camp and recorded his friends and family. He mirrored his father’s habit of recording family members with a video camera. He described his father as obsessed with filming and that the camera was a natural participant in their family’s lives. For his documentaries, Fleifel confessed that he found the most interesting characters in the people closest to him: his grandfather, childhood friends, and uncle. Perhaps it is this sense of nostalgic intimacy and community that Fleifel seeks to evoke through visual storytelling— he confessed that he misses the type of cinema that he grew up watching in the 70s and 80s.

“My first love is 1970s and 1980s Hollywood cinema. That’s what I grew up on before I knew how films were made. I wanted to pay a certain homage to that, especially buddy movies, whether it’s Midnight Run or Beverly Hills Cop or 48 Hours or Lethal Weapon. Those have all fed into the making of this film [‘To A Land Unknown’].”

— Mahdi Fleifel, to The Irish Times (2025)

His debut feature documentary was ‘A World Not Ours’ (2012) and it won 30 awards, including the Berlinale Peace Prize, the Edinburgh Grand Jury Prize, the Yamagata Grand Jury Prize, and the DOC:NYC Grand Jury Prize. He was named the Best New Nordic Voice at Nordisk Panorama, and received the New Talent Award at CPH:DOX in 2013. After ‘A World Not Ours’, Fleifel began to create short documentaries.

Of these, ‘A Man Returned’ (2016) won the Silver Bear at the Berlinale as well as being nominated for the Prix Berlin for the European Film Awards. ‘A Drowning Man’ was selected at Cannes and nominated for a BAFTA. ‘I Signed the Petition’ (2018) won Best Documentary Short at the IDFA and was subsequently nominated for the 2018 European Film Awards. ‘3 Logical Exits’ (2019) received the Bill Douglas Award at GSFF in 2020. His accolades span over 50 awards and 95 nominations in total.

Interview with Producer Geoff Arbourne

Luckily, Narratives of Resistance was able to meet the producer, Geoff Arbourne from Inside Out FIlms, after a screening of ‘To A Land Unknown’. He appeared at the Hong Kong International FIlm Festival for a short Q&A session with the audience– they were curious and asked about certain open-ended questions that the film did not answer, as well as his general experience while producing the feature film.

GA: Mahdi and I have been friends for over ten years, and we met in film school in London with a documentary background.

Geoff agreed to a quick chat with Narratives of Resistance after this Q&A session for our article.

Q: If you two have a dominant background in documentary film-making, what drove your discussion to make a feature film based on fictional characters?

GA: Well, because it has more of a reach. We wanted to have a film in cinemas— documentaries are rarely screened in cinemas, and we wanted this wider outreach [so the story could] speak to more people. Documentaries in contrast, are more narrow with their narrative potential and the audience it attracts.

In fact, Mahdi has been traveling since May 2024 to all those film festivals… The film has been shown in over 100 film festivals actually, and now it’s having its theatrical release in the USA, UK and France. Not everything is picked up by streaming services, like Netflix, where people watch everything nowadays.

Q: Are there any stories that you are allowed to share about how the genocide affected filming?

GA: We started filming in November 2023 and much of the crew is from Jordan, Syria and Lebanon. You can’t put [the film and going to work] out of context [of the events after October 7].

Q: Does that mean there was a tense atmosphere on set?

GA: It was very traumatic for the crew to go to set [because of the genocide], and many of them were sleeping on sets. We had to replace a cast member last minute because he couldn’t get past [Greek] immigration— they essentially said that, in better wording, that he looked too much like a refugee. [The immigration officers were concerned that we were going to smuggle in a refugee under the guise of filming a movie.] So we had to bring in someone else with a passport. Instead of the original Syrian actor, we got someone with a Jordanian passport.

Bringing people in [to Europe] was a nightmare.

But people still worked. Mahdi and Mahmoud [Bakri] felt that they had the obligation to work. Sitting around and staring at their phones, waiting for news, was traumatizing… so work became like a form of therapy for them.

Similar to a refugee’s sense of shame from deserting their family to live and pursue a life outside of the oppressive country they fled, one cannot help but wonder if the cast and crew carried their own feeling of survivor’s guilt. It may have been exacerbated by the dire consequences that happened in Palestine, as well as in Lebanon and Syria when the genocide continued. It is not just Fleifel’s personal curiosity and his wish to intimately explore other individuals’ vulnerable, broken moments of shame— through this film, you can’t help but to imagine that the crew became too familiar with it and survivor’s guilt.

It is notable for Arbourne to note Bakri alongside Fleifel’s determination to film. As the lead actor of the film, and the complex character of Chatila that he was tasked to perform, Bakri had enormous shoes to fill. It would be understandable that amid all of the stress related to the film, with the genocide as the cherry on top, Bakri would find it near impossible to work. However, he did. This ethic of his speaks to Bakri’s professionalism, dedication, and sense of responsibility.

Fleifel shared an anecdote about casting Bakri, saying:

“I was looking all over in Palestine, in Jordan, in Lebanon, in Athens … I remember telling my mother that we have the youngest son of Mohammed Bakri, and she said, ‘Oh, so it’s a real film’. They are known all over the Arab world … Because Palestinian cinema is so small, people just end up recycling the same cast. This is why I was reluctant to even work with Mahmoud, because I had already seen him.

But then he auditioned for us. He shaved his head. He had a completely different look. There was suddenly an edge to him. And I thought, ‘Okay, we are starting from a fresh place’.”

— Mahdi Fleifel, to The Irish Times (2025)

Initially, Fleifel wanted to cast unknown actors. He wanted to work with the right personalities who already embodied, or had some elements of, the characters that he could intuitively sense in the beginning– then bring it out in the later process of filming.

Q: I understand that filming and producing this artwork was a cathartic experience for them. How much of this film was based on reality and personal stories?

GA: The story is very personal to Mahdi; he grew up in Lebanon camps himself, and knows many people from different camps in Lebanon who got stuck in Athens on the way to the rest of Europe. A lot of the stories are from Mahdi’s friends.

This sounds like an understatement. In Fleifel’s previous works and documentaries, he has followed a main ensemble of four men. To name a couple— Abu Eyad, who starred in ‘A World Not Ours’ and ‘Xenos’; Reda from ‘A Man Returned’ and ‘3 Logical Exits’ who, like the fictional character in ‘To A Land Unknown’, sadly died from an overdose in Athens.

He started to film his childhood friends and their stories in Ein el-Hilweh in early 2000s, and Reda asked Fleifel why he didn’t make a film about him. Reda was the neighbour of Fleifel’s grandparents and knew him as the ‘guy always running around with the camera’. At first, he didn’t see any reason to; he saw that Reda was surrounded by drug dealers who frequently visited his house. Reda invited Fleifel to film his wedding. The rest is history.

In Fleifel’s experience, he explained that “Greece is the gateway to Europe if you’re coming from the Middle East”. Near the end of ‘A World Not Ours’, Abu Eyad went to Europe and found himself stranded in Athens. Fleifel followed him and began to document Abu Eyad’s situation. In another interview with The New Arab, Fleifel expressed that he “ended up in Greece and this whole new world opened [up to him] with these young men from the camps, stranded in this purgatory, trying to make it to Northern Europe.”

Q: Can you share any thoughts about how your position, as a foreigner, motivates you to help with the Palestinian cause?

GA: Well, it’s all because of a sense of solidarity isn’t it? I’ve been friends with Mahdi for over 10 years, and growing up in the U.K. I see the lives of Arabs and how they’re mistreated, and how those from Congo and Sudan are treated in South Africa, where I live now.

It’s my role as a producer to help facilitate these teams, these creative workers, and to provide a safe space for their storytelling.

Q: Can I also ask if the film received any backlash or troubles in the context of increased polarization and anti-Palestinian hate?

GA: Thankfully, we didn’t come across any of that. I think a perk of being an independent film and having no native funding [such as outsider sponsorships] is that we did not face any confrontation amid this increased censorship.

Displacement Statistics

Malik: “Why did you leave Lebanon?”

Reda: “Lebanon is not our country… Lebanon is like a prison, like Gaza.”

According to the International Organization for Migration, ‘forced migration’ is a migratory movement that involves force, compulsion or coercion. Meanwhile, ‘displacement’ is the movement of people who have been forced, obliged to flee, or to leave their homes or places of habitual residence, specifically to avoid:

The effects of armed conflict,

Situations of generalized violence,

Violations of human rights,

Natural or man-made disasters.

Similarly, ‘refugees’ are people who flee their country because of a well-founded fear of persecution, are outside their country, and are unable to return to it. In 2022, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees introduced a new category: ‘other people in need of international protection’. They include people who are outside their country or territory of origin, because they have been forcibly displaced across international borders and need international protection, despite not having claimed a particular status. These protections include protection against forced return, access to basic services for a temporary or long-term basis.

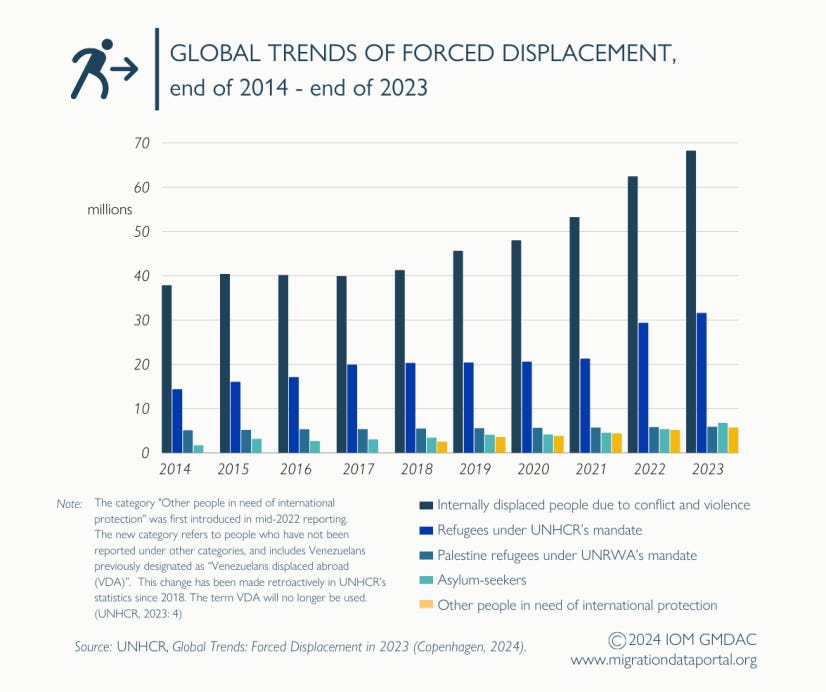

The total number of people forcibly displaced almost doubled over the past decade. At the end of 2014, there were around 59.5 million forcibly displaced people. However, this number rose to 117.3 million by the end of 2023, with an estimated 40% of them being children.

As of 2019, more than 5.6 million Palestinians were registered with the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). From this number, nearly one-third of the registered Palestine refugees (that’s over 1.5 million people) lived in 68 Palestinian refugee camps set up in Jordan, Lebanon, the Syrian Arab Republic, the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, including East Jerusalem. However, these numbers have likely risen exponentially since 2023. The plots of land that the camps are set upon are leased by the host country’s government from the local landowners. This means that the refugees in camps do not ‘own’ the land that their shelters are built on, but have the right to use this land for residence.

The largest number of refugees live in Jordan, where over 2 million registered refugees from the West Bank achieved full citizenship rights. However, Palestinians with roots in the Gaza Strip are still kept in legal limbo. However, usually they are denied this citizenship or legal residency in their host country, like for those in Syria and Lebanon. This means they have reduced rights: no right to vote, limited property rights, limited access to social services, and so on.

Greece on Refugees

“It’s like limbo. It’s a stopover in Europe, but it’s not the Europe that you’re interested in. It’s not the El Dorado of France or Germany. It’s very close to home in many ways. Economically, it’s difficult. The whole social fabric is different.”

— Mahdi Fleifel, to The Irish Times (2025)

Greece hosts around 50,000 registered refugees and 120,000 asylum seekers who have not yet achieved refugee status, however this has likely risen to unprecedented numbers since October 7. Many people fleeing violence from the Middle East and the South and Central Asia view Greece as an entry point to Europe, yet most of them end up remaining in the country. They can no longer legally travel deeper into Europe.

This is due to the European Union’s (EU) recent policies that increased border restrictions and other limitations on this vulnerable population. Despite the EU’s founding and commitment to international law and human rights for 60 years, Greece and Italy are now left to shoulder the responsibility of accepting refugees. Since the March 2016 agreement that restricted border crossings, around 16,000 refugees from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan remain stuck on Lesbos, Chios, Kos, Samos and Leros. An additional 38,000 refugees live on the Greek mainland. Many of these refugees are forced to live in overcrowded and dangerous situations as they wait months for their asylum cases to be heard. Moreover, they are unable to find work because of the aftermath of Greece’s 2015 financial crisis.

As a result, Greek border forces have been known to violently and illegally detain groups of refugees before forcing them back, with a note that violent pushbacks have become the de facto policy. Amnesty International published a 46-page report in 2021 that documents these serious human rights violations by the Greek authorities, including: blows with sticks or truncheons, kicks, punches, and slaps that resulted in severe injury, as well as humiliating and aggressive strip searches that amounted to torture due to their severity and intent.

Nowadays, the majority of refugees reaching Greece are children, not adult men. The numbers of unaccompanied minors reaching the country have doubled in 2024 compared to one decade ago. This overcrowding and influx have created a near-total halt of basic services for refugees in Greece: withdrawal of interpretation services in camps, persisting shortages in medical and psychosocial personnel, and the complete halt of the monthly financial allowance granted to asylum seekers. Many are at risk of immediate homelessness.

“What we are seeing amounts to a children’s emergency of the kind that we haven’t witnessed in years. There are a huge number of kids turning up on boats every day and an urgent need for the creation of more safe spaces to house them.”

— Sofia Kouvelaki, NGO Home Project

Greece’s migration minister, Nikos Panagiotopoulos, predicted that pressure on eastern Mediterranean migration routes to Greece, Europe’s southernmost border state, was likely to continue. Camps on the Aegean islands have reached full capacity, and hundreds of children in Samos, Leros and Kos live without clothes, shoes, and little-to-no access to essential services. The chronic legal and practical obstacles to refugees’ access to documents and socioeconomic rights in Greece remain unresolved, and this obstacle worsens when refugee children do not have an interpreter or guardian to guide them.

“The extensive geopolitical unrest in our broader region, where three wars are waging, the most recent in Syria, combined with the climate crisis, is forcing many to abandon their homes simply to survive. All these factors have led to a significant increase in migration and refugee flows since late 2023.”

Recently, the European Court of Human Rights has found Greece guilty of conducting systematic pushbacks of would-be asylum seekers, the first time that Greece was publicly condemned for carrying out a policy that it has long denied. The Greek Council for Refugees described the decision as a ‘landmark judgment’ as the Strasbourg court accepted a refugee’s allegation that she was illegally detained before being deported. Hopefully, this will open the pathway for the refugee situation in Greece to improve.

“Children fleeing humanitarian crises arrive in Greece hoping for safety but find themselves trapped in yet another crisis. Reception centres meant to shelter them have been places of fear and isolation, with violence, alarming living conditions and a lack of support services.”

— Willy Bergogne, Europe director at Save the Children

Thanks for reading our post reviewing To A Land Unknown (2024) directed by Mahdi Fleifel! All opinions stated in our review are held by Narratives of Resistance only— it does not represent the views of anyone else. If you have watched this film, leave a comment below or DM us for a chat! Please check out the hyperlinks if you want to learn more about Mahdi Fleifel, displacement statistics and trends, and Greece’s long and turbulent history regarding the refugee crisis.

Special thank you to Geoff Arbourne, who agreed to a quick interview for this article!

If you want to stay updated with our art and cultural engagements, subscribe to our Substack and follow us on Instagram @nor.films — we post event announcements, share charities, and other helpful resources to stay critically educated on resistance art.